Introduction

There is an increasing burden of coronary artery disease around the world1. Ischaemic heart disease remains the main cause of death globally2. With increasing age, frailty and comorbidities, senior patients aged 80 years old and above who develop ischaemic heart disease are at higher risk of mortality and other complications. Most guidelines from major cardiac societies have advocated for invasive treatment for patients who develop ischaemic heart disease, acute coronary syndromes (ACS; which include ST-elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI], and unstable angina [UA])3456. However, most of these guidelines were derived from evidence that studied younger patients, as senior patients aged 80 years old and above were often underrepresented7 and, hence, less invasively managed18. The paucity of data on senior patients aged 80 years old and above has also led to major cardiac societies to call for more studies in this age group89.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic review or meta-analysis thus far that examines the overall outcomes of senior patients aged 80 years old and above undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Recent studies have demonstrated the benefits of an invasive approach in senior patients aged 80 years old and above. This entailed selecting them for invasive coronary angiogram, and subsequently proceeding with the appropriate management plan which included coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), PCI, or optimal medical therapy (OMT)10. However, there are minimal studies describing the outcomes of performing PCI itself in this age group. Contemporary evidence has thus far proven survival benefits of an invasive approach in senior patients aged 80 years old and above with ACS and, to a lesser extent, morbidity benefits (in relieving anginal symptoms) in patients with stable heart disease11.

There is increased interest in the “oldest-old”, which is defined as people aged 80 years old and above, and the concept of successful ageing in this age group12131415. People in this age group are frailer, experience greater health decline, and have higher rates of hospitalisation, comorbidities and mortality. Even though they may reap the benefits of PCI in the context of ischaemic heart disease and myocardial infarction (MI), this needs to be balanced with the relative higher risk of harm from invasive interventions. Frailty not only contributes to the risk of mortality from the disease process itself but also from the intervention1617. To allow clinicians and interventionists to better manage patients in this age group, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to study the outcomes of PCI in senior patients aged 80 years old and above, regardless of their underlying indications (Central illustration).

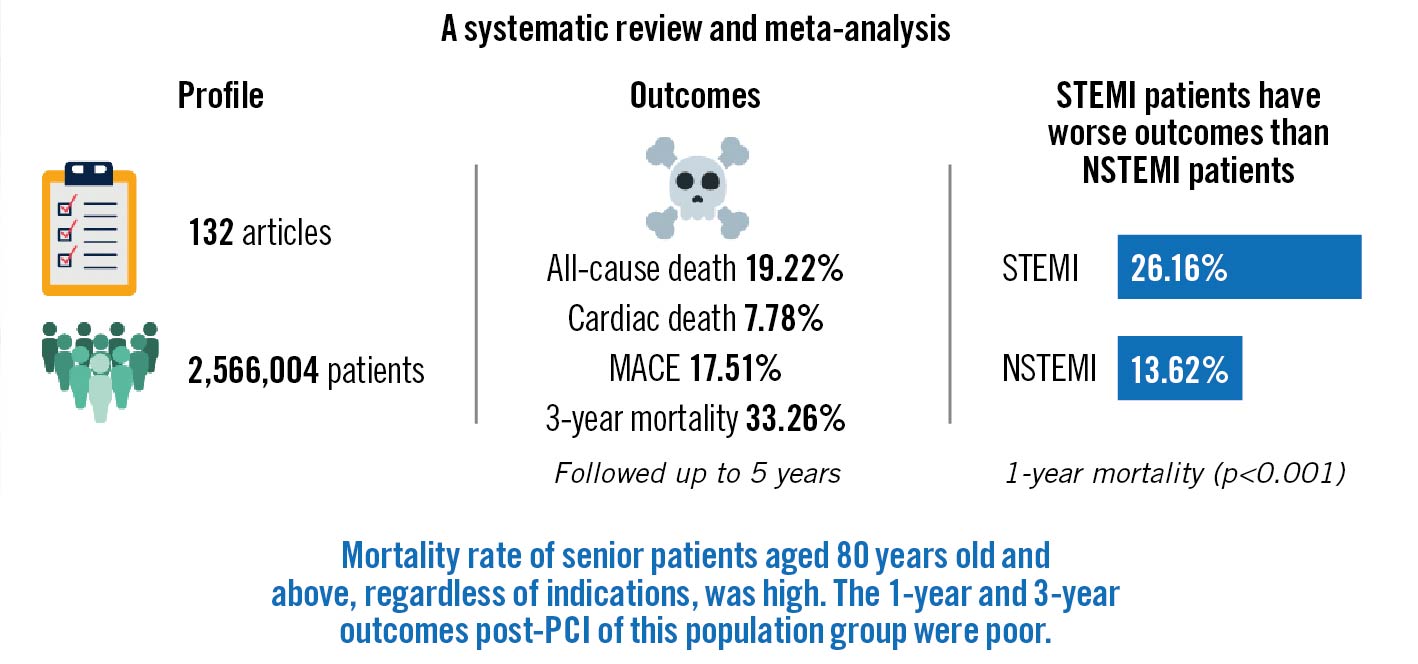

Central illustration. PCI outcomes in seniors aged 80 years old and above. MACE: major adverse cardiac events; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Methods

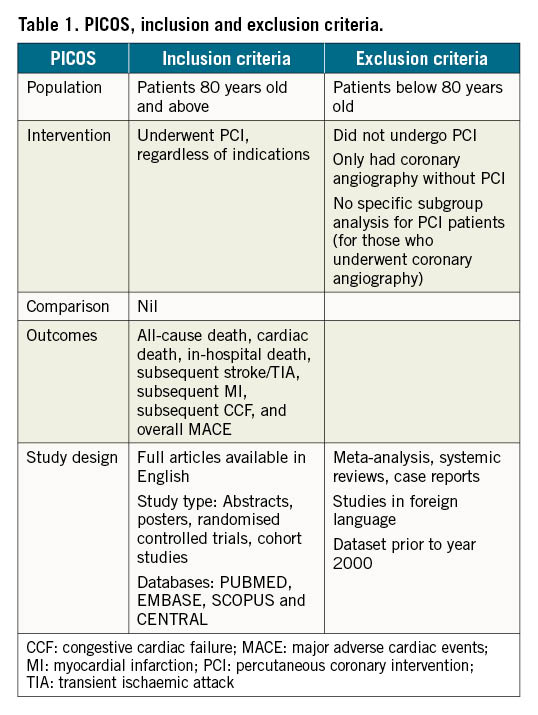

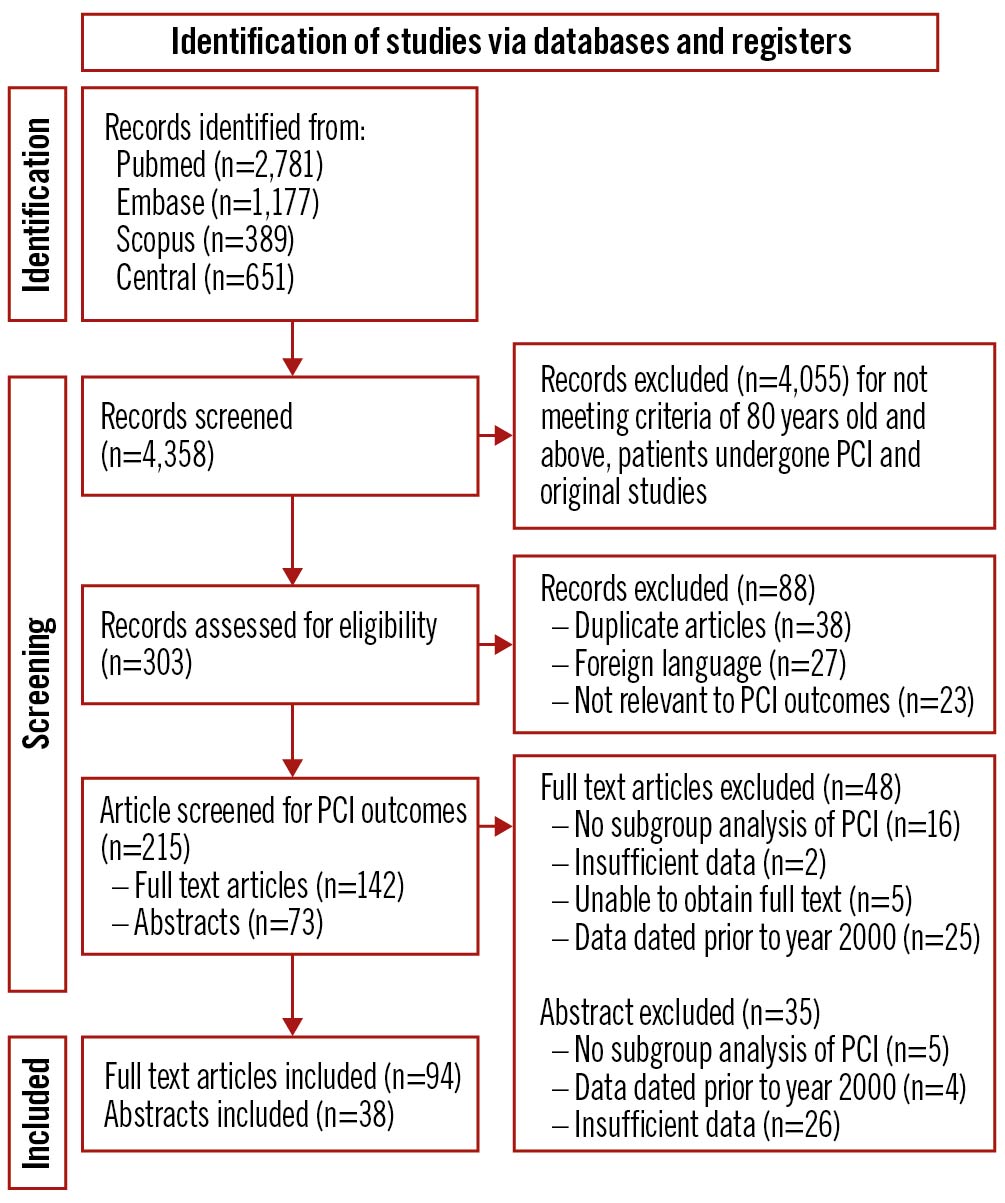

Ethics approval and consent to participate was not required for this study as this study used publicly available data. We searched 4 databases (PUBMED, EMBASE, SCOPUS and CENTRAL) in February 2021, with the following search terms: “percutaneous coronary intervention” OR “PCI” OR “myocardial revasculari*” OR “coronary angioplasty” OR “percutaneous coronary revasculari*” OR “primary PCI” OR “PPCI” OR “coronary stent” OR “balloon angioplasty” OR “coronary atherectomy” AND “elderly” OR “old age” OR “octogenarian” OR “older adult” OR “older age”. We identified studies that included PCI in patients who were 80 years old and above. Studies that only included coronary angiography without the use of PCI and studies that did not include the subgroup data of PCI were excluded. We included studies with all indications for PCI, including stable coronary artery disease and ACS. Only studies published in English were included. To keep the dataset contemporary, studies with data prior to the year 2000 were excluded, as drug-eluting stents (DES) were introduced in the early 2000s. Full papers were obtained either via retrieval from the databases or by contacting the relevant authors if the papers could not be obtained from the databases. Abstracts were included if they included the relevant parameters. We included all studies, according to the population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics included mean age, smoking history, history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, stroke, atrial fibrillation, congestive cardiac failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease and history of PCI or CABG. We then obtained the outcomes of all-cause death, cardiac death, in-hospital death, subsequent stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA), subsequent MI, subsequent congestive cardiac failure (CCF) which developed as a complication of MI, and overall major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). MACE was defined as a composite of death, stroke/TIA, MI, CCF, or revascularisation with either PCI or CABG. Data, which were reported in percentages, were converted to absolute numbers by calculation and rounded to the nearest whole number.

Statistical analysis

Extracted data were used to analyse the pooled cumulative incidence with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for outcomes of PCI. We calculated cumulative incidences utilising the 1-step generalised linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) method employing the metaprop_one routine in Stata (version 16.0; StataCorp). Compared to traditional 2-stage methods, this method is proven to produce smaller errors, less biased estimates, and greater coverage probabilities1819. When the 1-stage model failed to converge, a random-effects inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis using the Freeman-Tukey transformation was utilised to pool proportions. The random-effects model was adopted in all analyses to account for anticipated heterogeneity in the observational estimates20. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic21. An I² value of <30% indicates low heterogeneity between studies, an I² of 30-60% indicates moderate heterogeneity, and an I² of >60% indicates substantial heterogeneity. A 2-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Table 1)22. The various studies were appraised via the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3).

Results

The PRISMA flow chart is presented in Figure 1. A literature search of the 4 databases yielded a total of 4,358 results. Three researchers were involved in the screening process (N.H. Lin, J.S-Y. Ho and C-H. Sia). A total of 4,226 articles were excluded, according to the criteria described in the flow chart, and 94 full papers and 38 abstracts were ultimately included for the analysis and discussion in this paper. The pooled data from these articles were dated from 2000 to 2018. Thirty regions (Supplementary Table 4) were represented, and common sources of studies included the USA, Japan, the UK and Italy. Sixty-two out of 132 papers reported an ACS rate of more than 50%. A summary of the baseline characteristics is described in Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

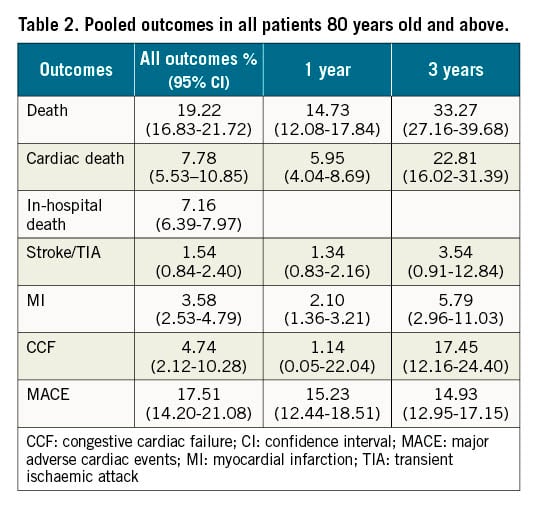

Pooled outcomes in all patients 80 years old and above

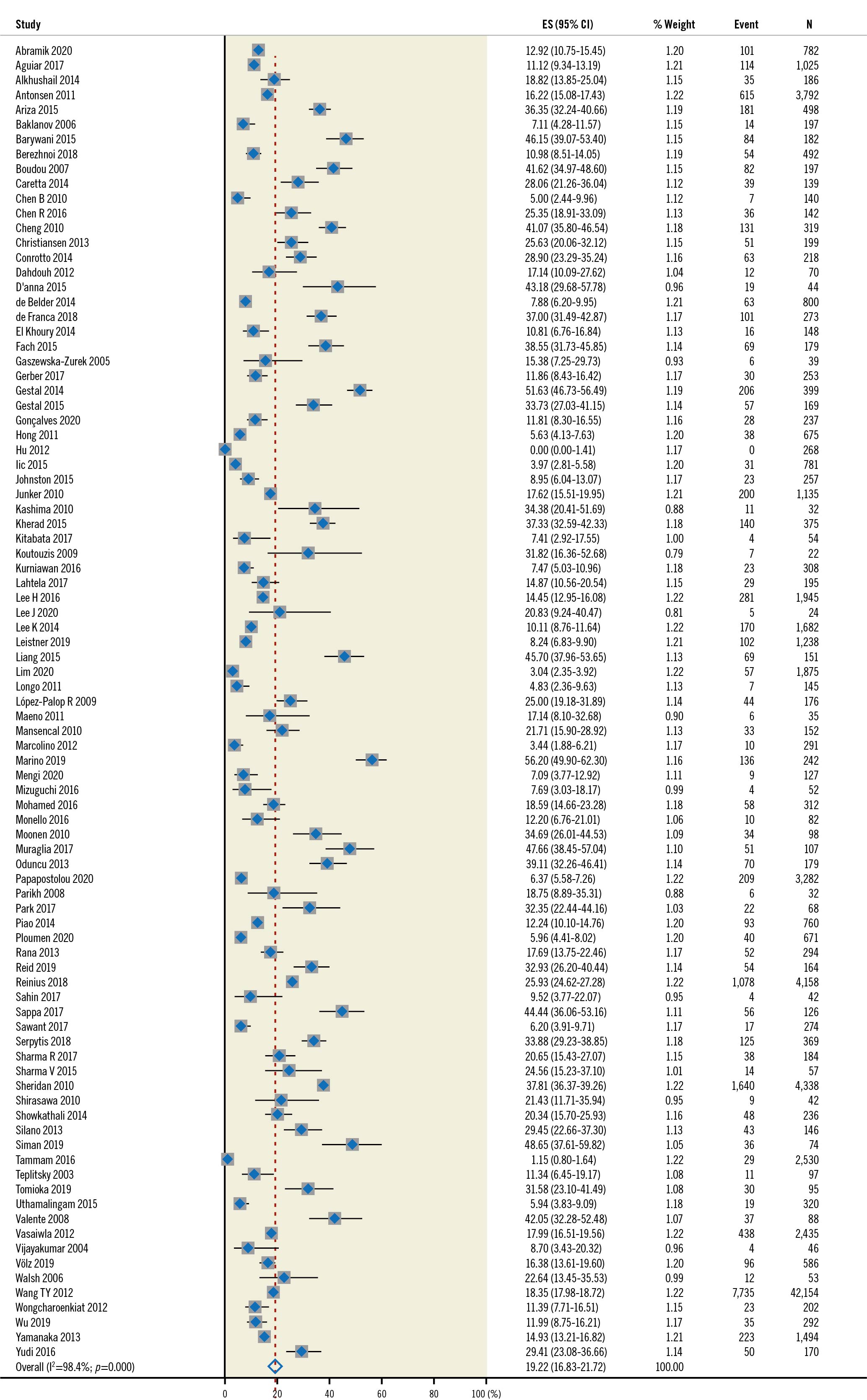

In total, we pooled 132 articles to form an overall cohort of 2,566,004 patients aged 80 years old and above in our meta-analysis, including all indications for PCI. The outcomes (Table 2) were as follows: the cumulative incidence of all-cause death (Figure 2) was 19.22% (95% CI: 16.83-21.72), cardiac death was 7.78% (95% CI: 5.53–10.85), in-hospital death was 7.16% (95% CI: 6.39-7.97), subsequent stroke/TIA was 1.54% (95% CI: 0.84-2.40), subsequent MI was 3.58% (95% CI: 2.53–4.79), subsequent CCF was 4.74% (95% CI: 2.12-10.28), and MACE was 17.51% (95% CI: 14.20-21.08). The overall follow-up period extended up to 5 years.

Figure 2. All-cause death in the overall population. CI: confidence interval; ES: effect size

One-year overall outcomes based on a pooled cohort of 36,919 patients from 52 articles and 3-year outcomes based on a pooled cohort of 6,169 patients from 9 articles demonstrated increasing rates of all-cause death (14.73% vs 33.27%), cardiac death (5.95% vs 22.81%) and subsequent CCF (4.74% vs 17.45%) over time.

Subgroup analyses

We were also able to perform a subgroup analysis of the clinical outcomes in STEMI and NSTEMI patients.

Pooled outcomes in STEMI patients

We pooled 27 articles to create a cohort of 106,343 patients who had ST-elevation myocardial infarction. In this cohort, the previous history of MI, PCI, and CABG in general (if reported) was less than 20%. The outcomes were as follows: the cumulative incidence of all-cause death was 23.08% (95% CI: 17.43-29.89), cardiac death was 9.42% (95% CI: 2.67-28.26), in-hospital death was 14.24% (95% CI: 12.09-16.53), subsequent stroke/TIA was 1.93% (95% CI: 12.09-16.53), subsequent MI was 3.68% (95% CI: 2.21-6.06), subsequent CCF was 13.08% (95% CI: 9.19-18.30), and MACE was 12.19% (95% CI: 5.11-26.35). The follow-up period extended up to 2 years, with most studies following patients up to 1 year.

Pooled outcomes in NSTEMI patients

We combined 7 articles to create a pooled cohort of 12,211 patients who had non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The previous history of MI was 20-40%, PCI 10%-20% and CABG 6-7% (if reported). The outcomes were as follows: the cumulative incidence of all-cause death was 14.74% (95% CI: 7.40-27.21), in-hospital death was 4.44% (95% CI: 2.65-7.36), subsequent stroke/TIA was 0.19% (0.07-0.50), subsequent MI was 1.55% (0.92-2.58), and MACE was 10.93% (95% CI: 9.79-12.18). The follow-up period extended up to 2 years, with most studies following patients up to 1 year.

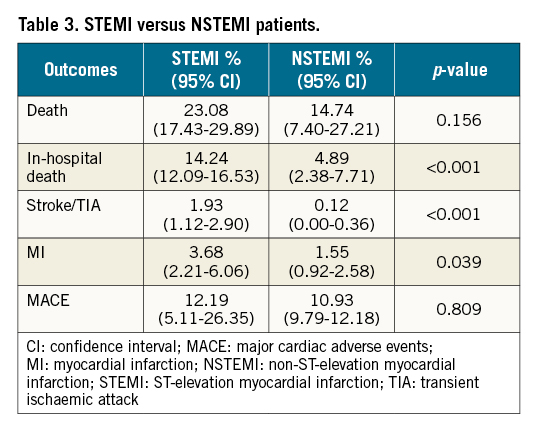

STEMI patients had more outcomes than NSTEMI patients

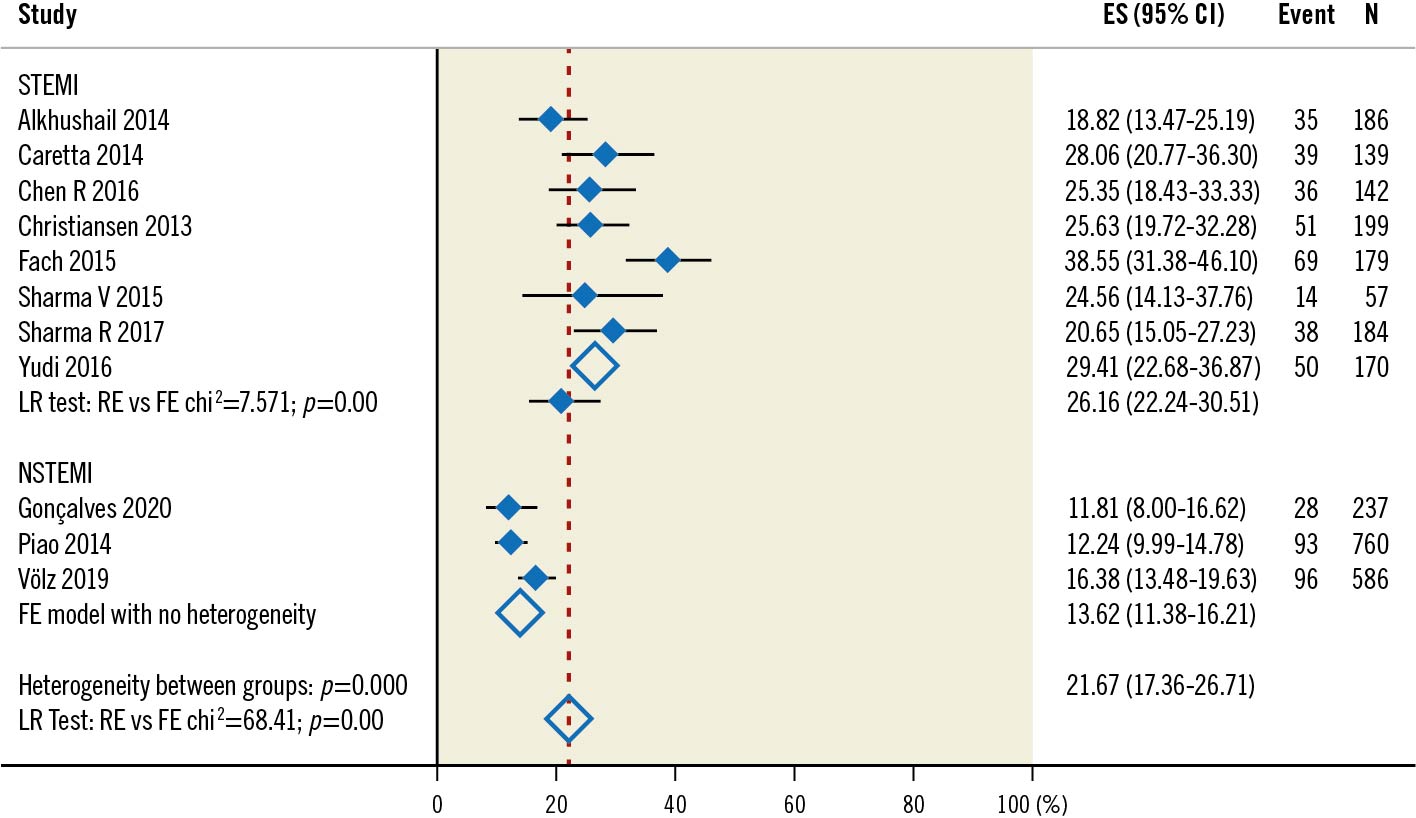

Overall, patients with STEMI had poorer outcomes as compared to NSTEMI patients (Table 3) in the outcomes of in-hospital death (STEMI 14.24%, NSTEMI 4.89%; p-value <0.001), subsequent stroke/TIA (STEMI 1.93%, NSTEMI 0.12%; p-value <0.001), and subsequent MI (STEMI 3.68%, NSTEMI 1.55%; p-value=0.039). There were no significant differences in all-cause death (STEMI 23.08%, NSTEMI 14.74%; p-value=0.156) and MACE (STEMI 12.19%, NSTEMI 10.39%; p-value=0.809). However, 1-year outcomes showed significant differences in all-cause death between STEMI and NSTEMI patients (STEMI 26.16%, NSTEMI 13.62%; p-value <0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Three-year all-cause death in NSTEMI and STEMI populations.. CI: confidence interval; ES: effect size; FE: fixed effects; LR: likelihood ratio; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; RE: random effects; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Ischaemic time

In studies that reported ischaemic time, senior patients often had longer ischaemic times than the younger population. For example, Helft et al24 reported a median time from onset of symptoms to intervention of 251 min (versus 195 min in a younger group with a mean age of 61 years). Fach et al25 and Papapostolou et al26 reported a door-to-balloon time of 58 min (versus 43 mins in patients younger than 75 years old) and 87 min (versus 77 min in patients younger than 80 years old), respectively.

Discussion

Based on our meta-analysis, in senior patients aged 80 years old and above who underwent PCI, there was a pooled cumulative incidence of all-cause death of 18.55%, in-hospital death was at 6.7% and cardiac death was at 7.6%. There was also a 17.89% prevalence of MACE. Moreover, STEMI patients experienced a higher rate of in-hospital death, subsequent stroke/TIA and subsequent MI. The death rate was higher than that of a younger population (6.5%, mean age 59 to 65) as described in another meta-analysis of 5 studies by Stergiopoulos et al27, and similar to those previously reported by Avezum et al in the more senior age groups (18.4%, mean age 87.8)28. However, this is not unexpected as senior patients often have more comorbidities and poorer prognostic factors2829.

This high mortality rate was likely contributed to by the prevalence of underlying cardiovascular disease since most studies reported at least a 50% incidence of ACS. Other factors that have been previously quoted in other studies as contributing to the outcomes include fear of discovery of serious illnesses, atypical symptoms that mask the diagnosis of ACS (silent MI), reduced mobility that impedes access to healthcare, and economic concerns with regard to affordability of care or the lack of a dedicated caregiver30313233, all of which contribute to delayed presentations. Cognitive impairment may also mask symptom presentation34.

Although the rate of all-cause death was 18.55%, cardiac death constituted only 7.6%, which highlights that non-cardiac causes were major contributors of death. Besides ischaemic heart disease, the next most common causes of death globally include stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lower respiratory infections (such as pneumonia)2. In this ageing population, senior patients have more chronic diseases than younger patients, which predispose them to increased rates of mortality. Senior patients often have other concomitant illnesses such as cancer, stroke, pneumonia, as well as urinary tract infection35. These patients are frailer, have poorer myocardial reserves and, therefore, are more vulnerable to stressors and clinical insults from illnesses such as myocardial infarction36. This competing risk of death, of which frailty is a proven indicator of mortality after PCI37, may explain the relative higher proportion of death being non-cardiac in nature.

Our analysis also demonstrated that STEMI patients had poorer outcomes as compared to NSTEMI patients. Notably, they had a higher cumulative incidence of in-hospital death (STEMI 14.24% vs NSTEMI 4.89%), stroke/TIA (STEMI 1.93% vs NSTEMI 0.12%) and MI (STEMI 3.68% vs NSTEMI 1.55%). When followed up for 1 year, they had a significantly higher rate of all-cause death (STEMI 26.16% vs NSTEMI 13.62%; p<0.001), and in-hospital death (STEMI 14.53% vs NSTEMI 7.02%). Due to the underlying pathophysiology of transmural infarct in STEMI, the effect of myocardial necrosis is more pronounced in the older age group. Senior patients with STEMI often have higher rates of post-MI complications, including various mechanical and electrical complications, leading to higher mortality rates3839. To determine the significance of the poorer 1-year adverse outcomes in STEMI patients as compared to NSTEMI patients necessitates closer follow-up in this subgroup of patients.

Longer-term 1-year and 3-year outcomes showed increasing cumulative incidences. For example, the mortality rate at 1 year was at 14.61% and 33.27% at 3 years. The 3-year outcomes were also particularly high, with a cumulative incidence of 22.81% for cardiac death, 3.54% for stroke/TIA, 5.79% for MI, 17.45% for CCF, and 14.93% for MACE. Clinicians may need to consider closer follow-up in the longer term. However, it is also important to note that the studies pooled for the 3-year outcomes included papers that compared CABG vs PCI outcomes4041, of which one study had patients with multivessel disease41, and one study had patients with left main disease42; hence, the data might have been confounded by the severe underlying disease. However, more studies are required to further explore the implications of these observations and to determine if current clinical practice is sufficient to manage the long-term outcomes of senior patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

Although the risks of PCI in patients aged 80 years old and above were higher than in the younger population, current evidence still points towards the benefits of PCI in reducing death, cardiac death, and MI in patients with unstable coronary artery disease in the general population43. Such benefits are still seen in the senior population, mainly in the context of ACS1044. Hence, in line with most cardiac society recommendations, invasive revascularisation should still be offered to patients aged 80 years old and above with ACS, given its mortality benefit. Overall, clinicians need to appreciate the high cumulative incidence of various clinical outcomes in senior patients who have undergone PCI, taking into consideration the patient’s quality of life and goals of care, and individualise the treatment regime where appropriate.

Limitations

Our meta-analysis consisted of multiple studies examining this topic, which spanned many countries in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. This renders our findings applicable to an ethnically diverse population. However, we acknowledge a few limitations. Most of the articles included were observational studies, and there were few randomised controlled trials. However, randomised controlled trials are difficult to perform in this population, for reasons including difficulty in obtaining informed consent and difficulty in compliance to study protocol. Also, the investigators’ concerns of potential negative trial results if senior patients are enrolled, due to their multiple comorbidities, may lead to a selection bias against senior patients. 45. Hence, they should be the continued focus of future studies. As many articles included data that crossed from the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, we were unable to review temporal trends over the past 2 decades. As such, we were not able to exclude studies with the patients treated prior to the year 2010, and this may potentially confound our results. During this period, there was a shift towards the use of DES; hence, further studies are required to specifically examine differences between the pre-DES and DES eras. Furthermore, although frailty and sarcopenia are concepts that are gaining traction, most studies have yet to include frailty or sarcopenia in their assessment, thereby making it difficult to assess their effect on PCI outcomes. Lastly, there is variation in STEMI systems of care across various countries, and the ischaemic time was not well reported in many studies, which might have potentially affected the outcome.

Conclusions

There was a high mortality rate at 1 year and 3 years post-PCI in the overall population of senior patients aged 80 years old and above, regardless of indication. This necessitates further studies to explore the implications of these observations.

Impact on daily practice

With the increasing burden of coronary artery disease, especially in senior patients aged 80 years old and above, more studies are required to study the implications of the high mortality rate at 1 year and 3 years post-PCI, regardless of indication.

Funding

Ching-Hui Sia was supported by the National University of Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine’s Junior Academic Faculty Scheme

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.