Introduction

Fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with a favourable outcome compared to angiography-guided PCI1,2. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement is conducted under maximum hyperaemic conditions induced by intracoronary or intravenous administration of a vasodilator, which may cause side effects including vomiting, hypotension, and arrhythmia3,4. Recently, resting non-hyperaemic indices, including the instantaneous wave free ratio (iFR), have been developed to assess the functional severity of coronary stenosis5. iFR and other resting indices do not require the induction of hyperaemia, and thus hyperaemia-related complications are avoidable3,4. Another important advantage of iFR is that post-intervention iFR is predictable in a sequential or diffuse coronary lesion by the following simple equation6,7: iFRpost=iFRpre+ΔiFR. Prediction of post-intervention FFR is usually considered difficult in FFR due to complex haemodynamic interactions between the individual stenoses under maximum hyperaemia8,9. Therefore, the current recommendation for a sequential or diffuse coronary lesions is to measure FFR distally, and perform a pressure pullback under maximum hyperaemia. Treatment of the most severely narrowed lesion is then determined by which of the lesions produces the largest ΔFFR10,11,12.

We consider that another factor that makes post-intervention FFR prediction in a diffuse/sequential lesion difficult is the existence of an intra-stent pressure gradient after intervention. The post-intervention intra-stent pressure gradient inevitably affects the post-intervention FFR13,14,15,16. We hypothesised that post-intervention FFR, in a diffuse/sequential coronary lesion, is predictable if the post-intervention intra-stent FFR is considered. Thus we developed a mathematical equation to predict post-intervention FFR in diffuse/sequential lesions by considering the intra-stent FFR gradient. The main purpose of the present study is to validate the equation in an in vitro circuit model and in clinical data.

Methods

DERIVATION OF THE EQUATION

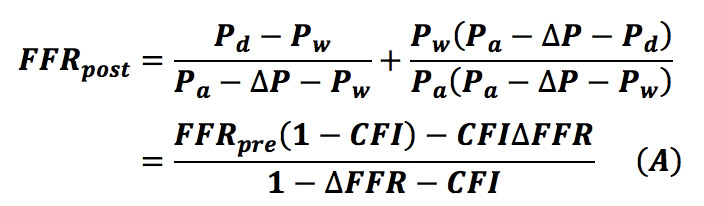

De Bruyne et al described theoretic equations to predict the FFR of each stenosis in a tandem lesion8, but their application is limited to tandem lesions. We mathematically generalised the equations to be applicable to a diffuse/sequential coronary lesion in a previous study (Equation A)9.

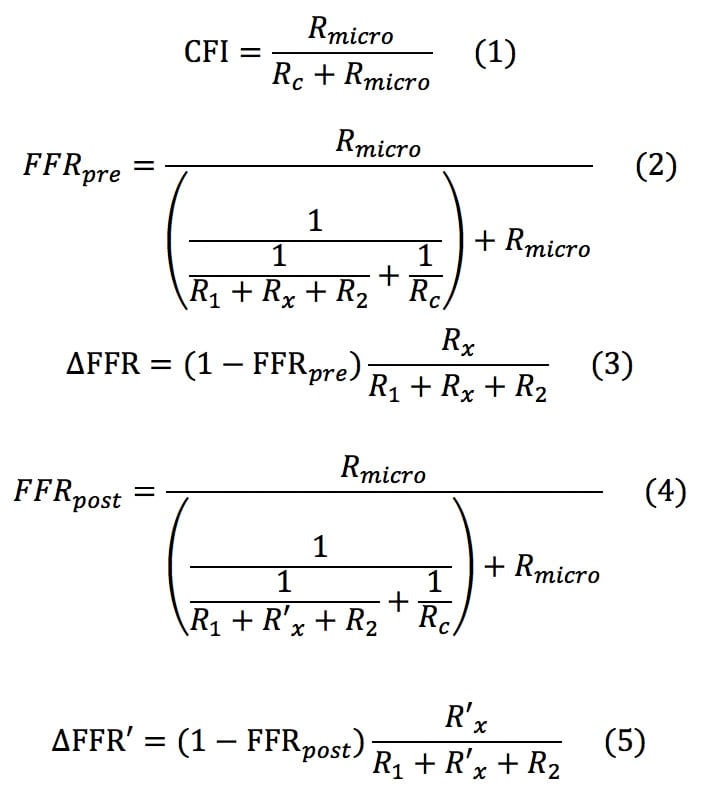

We wanted to formulate a novel equation in which post-intervention trans-stent FFR is considered. Consider a coronary circulation model simulating the diffuse/sequential coronary lesion with a collateral circulation (Figure 1). The abbreviations were defined as follows: Rs, resistance of the target coronary stenosis; R1, summed resistance of the proximal stenoses; R2, summed resistance of the distal stenoses; Rmicro, hyperaemic microcirculatory resistance; Rc, resistance of the collateral circulation; Pa, aortic pressure; Pprox, pressure proximal to Rs; Pdist, pressure distal to Rs; Pd, the most distal coronary pressure; Pw, coronary wedge pressure; and Pv, central venous pressure. The pre-intervention FFR was defined as FFRpre=(Pd–Pv)/(Pa–Pv)≓Pd/Pa because Pv was usually considered to be zero while deriving the FFR indices. Pre-intervention FFR gradient across the target lesion was defined as ΔFFR=(Pprox–Pdist)/Pa. The parameter calculated from (Pw–Pv)/(Pa–Pv)≓Pw/Pa was originally named “fractional flow reserve of the collateral artery (FFRcoll)”. Later, the name “pressure derived collateral flow index (CFI)” was used for this parameter17. Because the collateral flow reserve of the collateral artery is usually called “pressure derived CFI” in other studies, we adopted this terminology to avoid confusion. All the post-intervention parameters have been expressed by adding a prime to the pre-intervention parameters; thus, R’s indicates the resistance of the target coronary lesion after PCI and FFRpost=P’d/Pa and ΔFFR’=(P’prox–P’dist)/Pa are obtained. The pressure gradient across the stenosis was proportional to the flow because the flow was assumed to be the Hagen-Poiseuille flow in this model. Thus, the coronary circulation model can be considered analogous to an electric circuit. Figure 1 also describes the electric circuit that corresponds to the coronary circulation model. Under this assumption, the FFR indices can be expressed in terms of resistance as follows:

By solving the above equations (1) to (5), the following Equation (B) is obtained:

The detailed process of derivations of Equation B is given in Appendix 1.

Figure 1. Schematic model representing the coronary circulation with a sequential lesion and a collateral circulation. (A) Before coronary intervention. The resistance of the target lesion is expressed as Rs. (B) After coronary intervention. The resistance of target lesion changes to Rs’.

IN VITRO EXPERIMENT

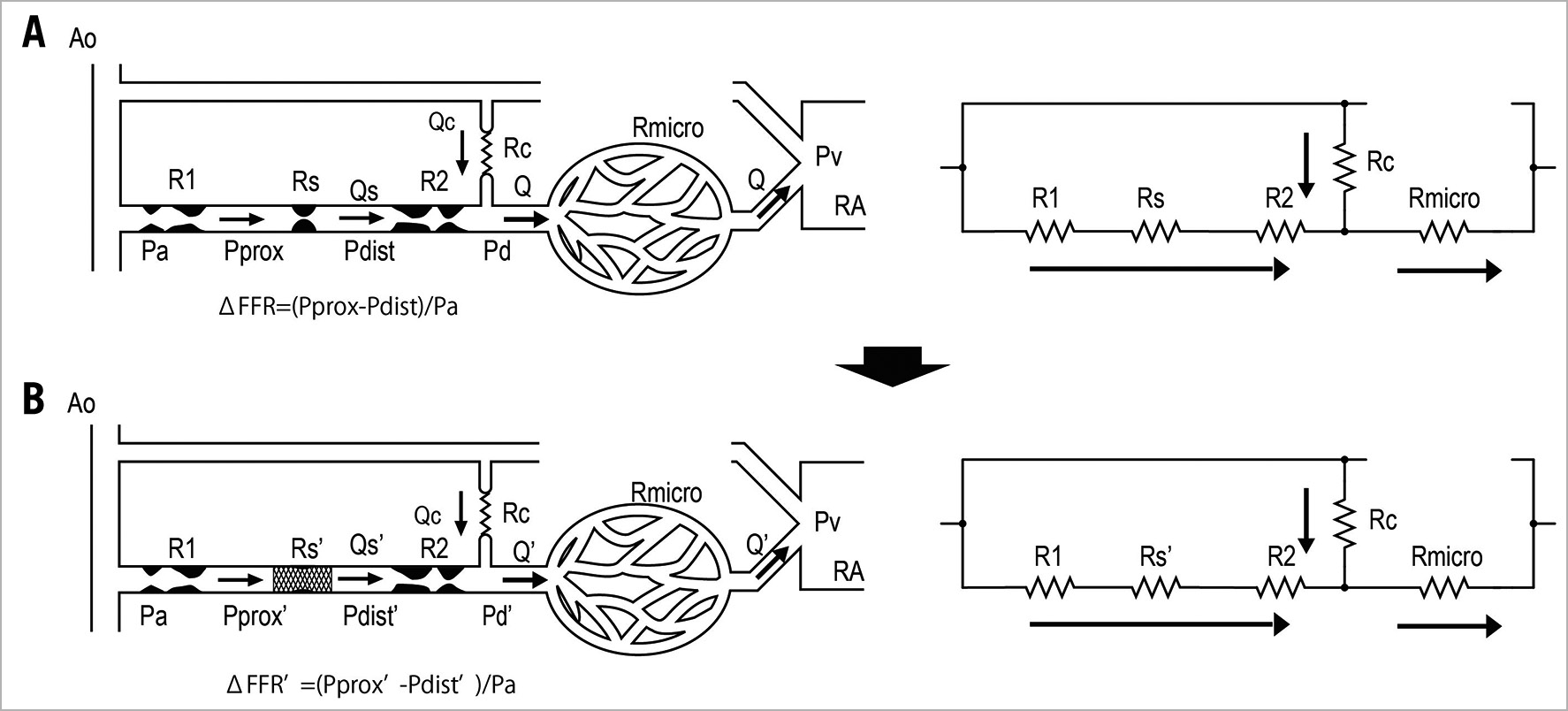

The experimental system was similar to that described in our previous studies (Figure 2). It consisted of a pump, systemic circulation, coronary circulation, and 5 constrictors placed in the coronary circulation. The pump produced a pulsatile flow at 60 rpm. The pressure and flow in the coronary artery could be adjusted by a valve placed in the aorta and constrictors placed in the coronary circulation. The coronary flow was approximately 300 to 500 mL/min. The circulating fluid was a 33% glycerine and 67% water a mixture comparable to the viscosity of blood. The systemic and coronary circulations were made of silicone rubber tubes that mimic the human arterial system. The inner diameter of the coronary artery was 4 mm and the inner diameter of the aorta was 12 mm. The constrictors made variable stenoses in the coronary artery by a screw rotation movement. The constrictor names correspond to the names of the resistances in the schematic model in Figure 1. FFR measurements were conducted using three 0.014 inch pressure wires (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA), one placed in the proximity of Rs, another placed distally to Rs, and one placed distally to R2.

Figure 2. In vitro experimental system. (A) The simulation system comprising a pump as well as systemic and coronary circulation. (B) Three pressure wires are placed in the coronary circulation: one placed proximally to the target stenosis (black arrow), another placed distally to the target stenosis (blue arrow), and the last one placed in the most distal point of the coronary circulation (red arrow).

The experiment was conducted in the following sequence. Variable degrees of coronary microcirculation and collateral circulation were randomly created by the constrictors. Variable degrees of three sequential coronary stenoses were randomly generated. Then, Pa, Pprox, Pdist, and Pd were recorded by using three pressure wires, and FFRpre and ΔFFR were calculated. Pw was obtained during a temporary occlusion of the distal part of the coronary artery, and pressure derived CFI was calculated. After partially releasing the stenosis of the target stenosis (Rs), P’prox, P’dist, and P’d were recorded, and then FFRpost and ΔFFR were calculated. The apparent FFR after partially releasing the target stenosis (FFRapparent) was defined as FFRapparent=FFRpre+ΔFFR, and the predicted value of FFR (FFRpredicted) was calculated using Equation A. The adjusted value of FFR considering the residual pressure gradient across the target stenosis (FFRadjusted) was calculated using Equation B. FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were compared with FFRpost.

CLINICAL DATA ANALYSIS

Consecutive patients who underwent elective coronary intervention for diffuse/sequential coronary lesions in Gifu Heart Center between March 2017 and March 2018 were included in the study. The inclusion criteria required all physiological parameters including FFRpre, ΔFFR, CFI, FFRpost, and ΔFFR’ to be obtained. The data in this study consisted of 67 coronary diffuse/sequential lesions from 67 patients. As all data were retrospectively collected from the patients’ records, the requirement of written informed consents was waived. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Coronary angiography and pressure wire assessments of coronary stenoses were conducted using the conventional approach. Briefly, the patients were instructed not to consume caffeine for 12 hours before the procedure, and PCI was performed through the radial approach using a 6 or 7 Fr system. Intracoronary nitrates (300 ug) were administered to all patients before pressure wires (OptoWire™; Opsens Medical, Quebec, Canada) were introduced. Equalisation was performed 1 to 2 mm distal to the guiding catheter. The distal position of the pressure wire was documented by angiography. Angioplasty was performed using second-generation drug-eluting stents, which were all optimised using imaging devices such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Maximum hyperaemia was induced by intravenous administration of adenosine. The pull-back recordings were conducted during maximum hyperaemia before and after PCI, and FFRpre, ΔFFR, FFRpost, and ΔFFR’ were obtained. Wedge pressure was recorded as the coronary pressure distal to the occluding balloon at 30s after the balloon occlusion, and pressure derived CFI was also obtained for all patients. Like in the in vitro experiment, FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were calculated from FFRpre, CFI, ΔFFR, and ΔFFR’, and compared with FFRpost. It is well-known that ΔFFR’ is obtained after PCI, and the coronary wedge pressure is not usually measured in real-world clinical practice. Equation B cannot be applied in clinical practice in this form. Thus, we calculated ΔFFR’/mm defined as ΔFFR’ by total stent length (mm) and estimated ΔFFR’ calculated as ΔFFR’/mm multiplied by the implanted stent length (ΔFFR’estimated). The estimated value of CFI (CFIestimated) was obtained using the average value of CFI from this study. FFRfixed-adjusted was calculated by using ΔFFR’estimated and CFIestimated in Equation B. FFRfixed-adjusted was compared with FFRadjusted.

STATISTICS

FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were compared with FFRpost using linear regression analysis and the Bland-Altman plot in the in vitro experiment and the clinical data analysis. The absolute differences of FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted to FFRpost were compared using a paired t-test for the in vitro experiment and in the clinical data analysis. The correlation coefficient and Bland-Altman plot of FFRfixed-adjusted to FFRpost were calculated, and the absolute difference of FFRfixed-adjusted to FFRpost was compared with that of FFRadjusted to FFRpost in the clinical data analysis. All continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation unless otherwise stated. A two-sided p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant in this study.

Results

IN VITRO EXPERIMENT

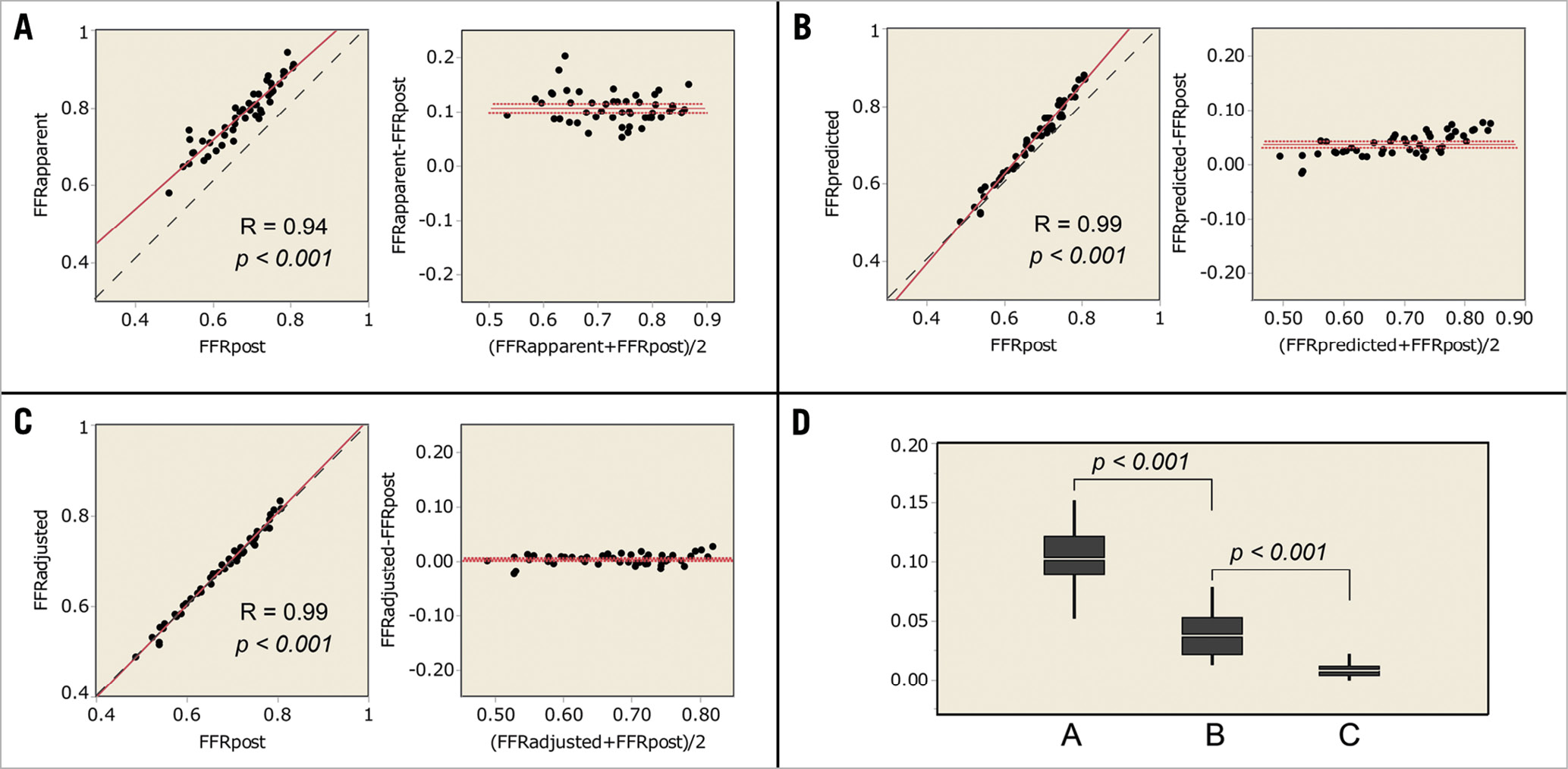

In the in vitro experiment, the procedures were repeated 50 times with changing degrees of each stenosis. Fifty different sets of pressure data were obtained in the in vitro experiment. FFRpre, CFI, and ΔFFR were 0.60±0.08, 0.29±0.08, 0.17±0.06, respectively. After partially releasing the target stenosis, ΔFFR’ and FFRpost were 0.05±0.02 and 0.67±0.08. FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were 0.78±0.08, 0.71±0.10, and 0.68±0.09. The correlation coefficients of FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were 0.94, 0.99, and 0.99 (Figure 3). The absolute differences of FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted to FFRpost were 0.11± 0.03, 0.04±0.02, and 0.008±0.006, respectively (p<0.001, paired t-test). Equation B predicted the post-intervention FFR with a 1.3±1.0% error. The results indicated that Equation B perfectly predicted post-intervention FFR of diffuse/sequential coronary lesions when considering the residual FFR gradient in the in vitro experiment.

Figure 3. Results of the in vitro experiment. (A-C) Linear regression and Bland-Altman plots. The dotted line is the line of identity. (A) FFRapparent compared with FFRpost. (B) FFRpredicted compared with FFRpost. (C) FFRadjusted compared with FFRpost. D) The absolute differences to FFRpost. A, the absolute difference of FFRapparent to FFRpost. B, the absolute difference of FFRpredicted to FFRpost. C, the absolute difference of FFRadjusted to FFRpost.

CLINICAL DATA ANALYSIS

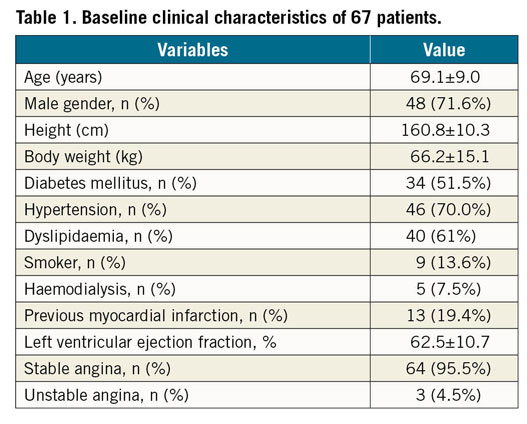

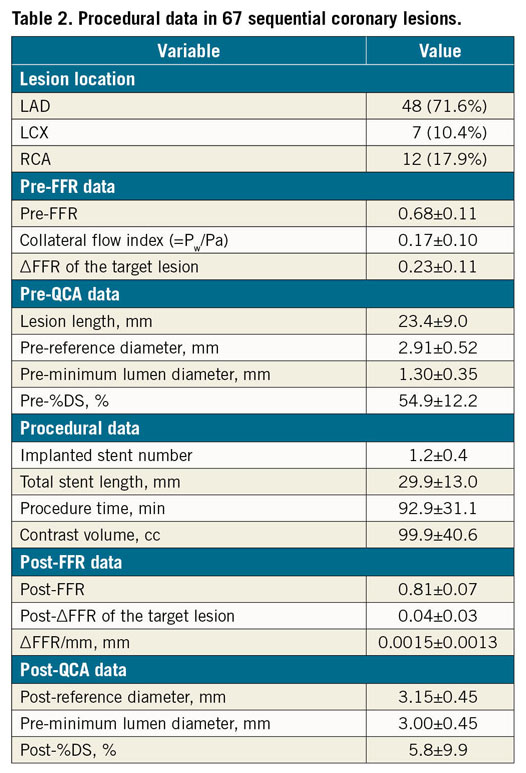

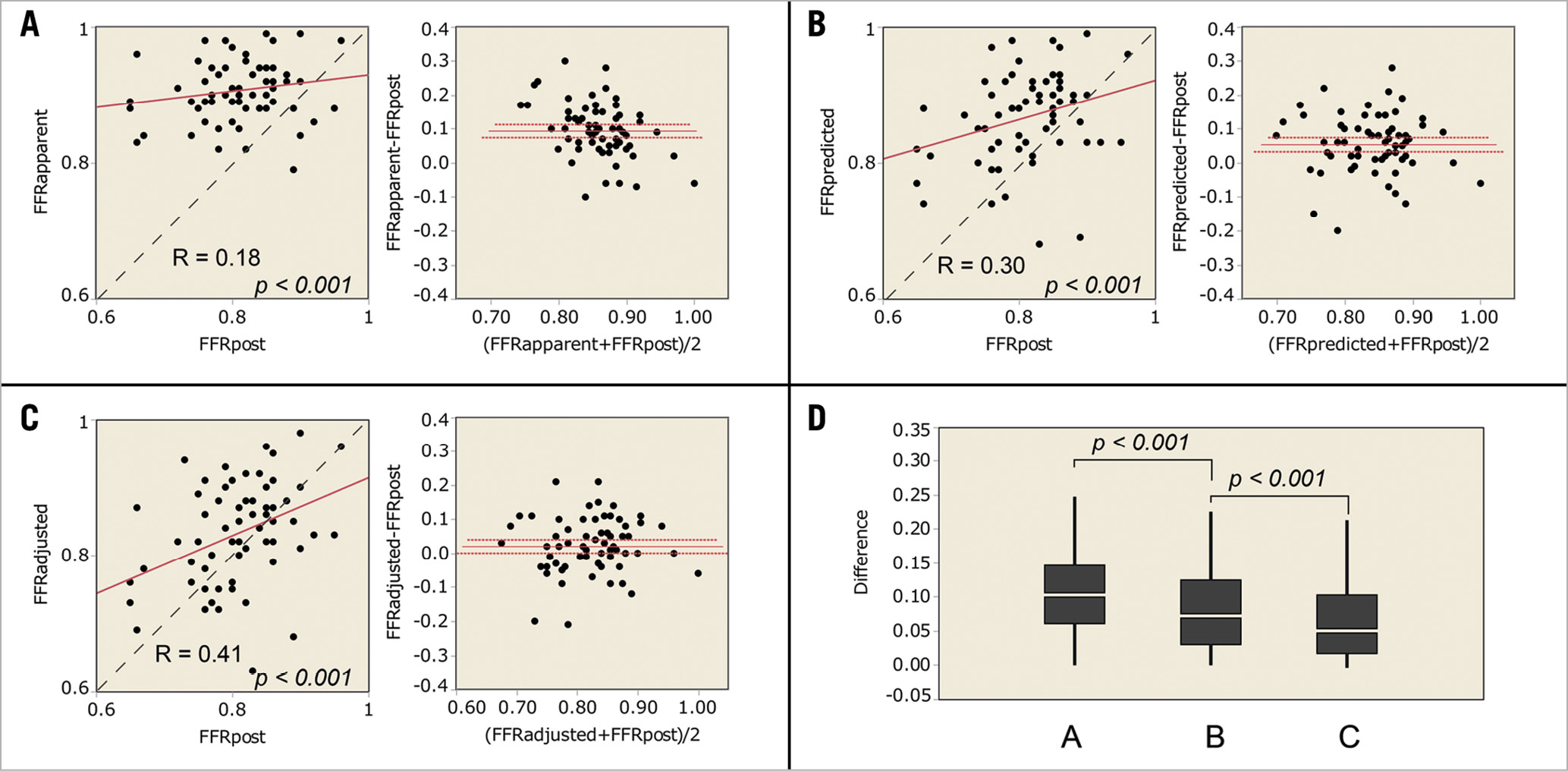

Sixty-seven coronary diffuse/sequential lesions from 67 patients were analysed. Patients’ demographics are summarised in Table 1. Briefly, the average age was 69.1±9.0 years old, and 48 patients (71.8%) were of male gender. Clinical presentations included 64 patients (95.5%) with stable angina and 3 patients (4.5%) with unstable angina. Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and STEMI patients were not included in the study. Lesions and procedure characteristics are listed in Table 2. The locations of the lesions were 48 lesions (71.6%) in the left anterior descending artery (LAD), 7 lesions (10.4%) in the left circumflex artery (LCX), and 12 lesions (17.9%) in the right coronary artery (RCA). All lesions were de novo coronary lesions. Stenosis diameter of the target lesion was 54.9±12.2%, reference vessel diameter was 2.91±0.52 mm, lesion length was 23.4±9.0 mm, and the minimum lumen diameter was 1.30±0.35 mm obtained by quantitative coronary angiography (QCA). The preprocedural intravenous adenosine induced FFR (FFRpre), ΔFFR of the target lesion, and CFI were 0.68±0.11, 0.17±0.10, and 0.23±0.11, respectively. All target lesions were treated by implanting a second-generation drug-eluting stent without any complications. The procedure time was 92.9±31.1 min and the contrast volume was 99.9±40.6 cm3. The total number of implanted stents was 1.2±0.4, and the total stent length was 29.9±13.0 mm. In post-procedural QCA, the reference diameter was 3.15±0.45 mm, the minimum stent diameter was 3.00±0.45 mm, and the diameter stenosis was 5.8±9.9%. The postprocedural adenosine induced FFR (FFRpost) was 0.81±0.07, ΔFFR of the stented lesion (ΔFFR’) was 0.04±0.03, ΔFFR’/mm was 0.0015±0.0013. FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were calculated from the obtained data and were 0.91±0.05, 0.87±0.07, and 0.83±0.08, respectively. The correlation coefficients of FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted were 0.18, 0.30, and 0.41, (p<0.001, Figure 4). The absolute differences of FFRapparent, FFRpredicted, and FFRadjusted to FFRpost were 0.11±0.06, 0.08±0.06, and 0.06±0.05, respectively (p<0.001, paired t-test). Equation B was used to calculate the post-intervention FFR with an 8.0±7.0% error.

Figure 4. Results of the clinical data analyses. (A-C) Linear regression and Bland-Altman plots. The dotted line is the line of identity. (A) FFRapparent compared with FFRpost. (B) FFRpredicted compared with FFRpost. (C) FFRadjusted compared with FFRpost. D) The absolute differences to FFRpost. A, the absolute difference of FFRapparent to FFRpost. B, the absolute difference of FFRpredicted to FFRpost. C, the absolute difference of FFRadjusted to FFRpost.

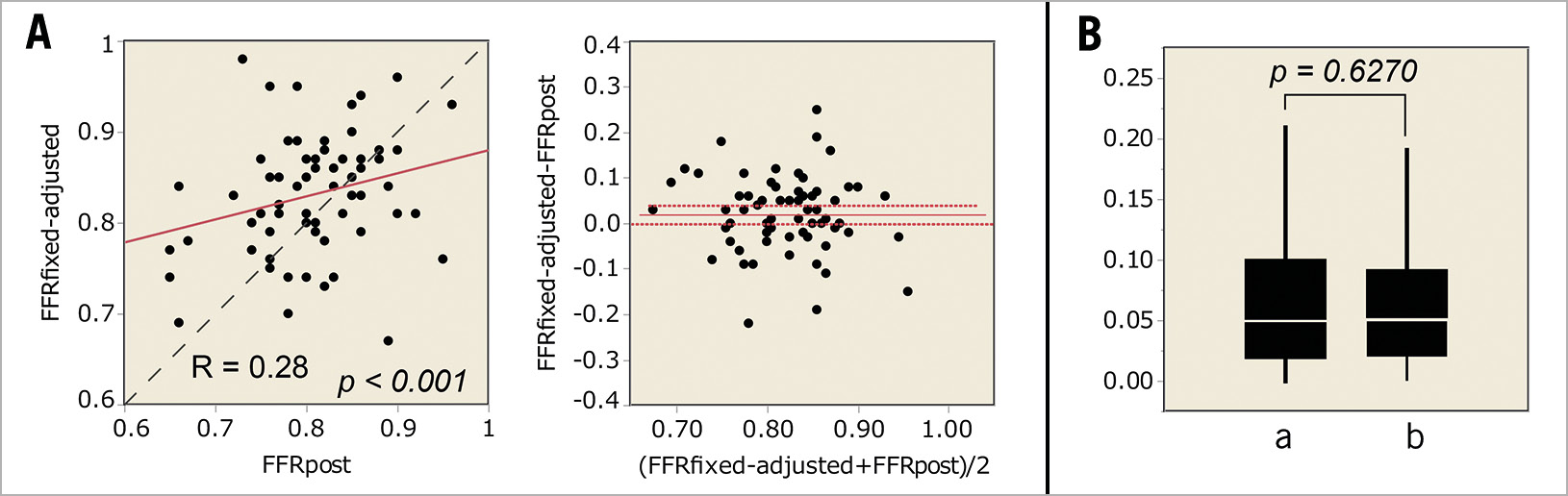

When the average value of CFI of 0.17 and ΔFFR’/mm of 0.0015 were applied to Equation B, FFRfixed-adjusted was obtained. FFRfixed-adjusted was 0.83±0.07, and the correlation coefficient of FFRfixed-adjusted to FFRpost was 0.28 (p<0.001, Figure 5). The absolute difference of FFRfixed-adjusted to FFRpost was 0.06±0.06, which was not significantly different from FFRadjusted to FFRpost (p=0.6420, paired t-test). Equation B predicted the post-intervention FFR with an 8.0±7.2% error.

Figure 5. Estimated FFR value using fixed value of CFI and ΔFFR in clinical data analyses. A) Linear regression and Bland-Altman plots. B) The absolute differences. a – the absolute difference of FFRadjusted to FFRpost. b – the absolute difference of FFRfixed-adjusted to FFRpost.

These results indicated that the accuracy of postprocedural FFR improved by taking the residual intra-stent FFR gradient into account, and the application of a fixed value of CFI and intra-stent FFR gradient did not significantly lower the accuracy of the post-procedural FFR prediction. However, the prediction error of approximately 8% is considered too large for clinical practice use.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study, which included the development of a novel equation which predicts the post-intervention FFR in diffuse/sequential coronary lesions, were that: the novel equation perfectly predicted post-intervention FFR of diffuse/sequential coronary lesions in the in vitro model of coronary circulation; in the clinical data analysis, prediction accuracy of post-intervention FFR in diffuse/sequential coronary lesions improved by taking the residual intra-stent FFR gradient into account and; the application of a fixed value of CFI and intra-stent FFR gradient did not significantly lower the accuracy of post-procedural FFR prediction. However, the prediction error in post-procedural FFR is considered too large to be used in clinical practice.

Previous studies have shown that PCI for stable angina is only beneficial in patients with significant myocardial ischaemia18,19. Although FFR has been regarded as the gold standard index for the invasive assessment of the physiological severity of coronary stenosis, the worldwide use of FFR remains low at around 5-10% of all PCIs20. The reasons for the low utilisation of FFR include the need for administration of hyperaemic agents, which is time consuming and may cause unpleasant complications3,4. Recently, resting indices including iFR have been developed to assess the functional severity of coronary stenosis. iFR is calculated by dividing the distal coronary pressure by the aortic pressure during the wave-free period under resting conditions. During the wave-free period, resistance in the cardiac cycle is considered to be minimal and constant. Following the results of two large randomised trials3,4, the current European guideline has updated iFR-guided revascularisation for stable angina to class I21. With the success of iFR, other resting indices, including the resting full-cycle ratio (RFR) and the diastolic pressure ratio (dPR) have been introduced21,22. The main advantage of these resting indices over FFR is that they do not require the induction of hyperaemia, thus hyperaemia-related complications are avoidable. Another advantage is that post-intervention indices are predictable because resting coronary flow is maintained constant due to autoregulation of the coronary circulation. Kikuta et al described that iFR pullback predicted the physiological outcome of PCI with a high degree of accuracy6,7.

On the other hand, predicting post-intervention FFR is considered difficult in diffuse/sequential coronary stenoses because complicated haemodynamic interactions exist between individual coronary stenoses. De Bruyne et al described theoretical equations to predict the FFR of each stenosis in a tandem lesion8, but its application was limited to tandem lesions. Thus we developed an equation which can be used in a diffuse/sequential coronary lesion (Equation A)9. However, the calculation requires coronary wedge pressure measurements, which makes the application of the equation in clinical practice difficult. Therefore, when using FFR to evaluate a sequential or diffuse coronary lesion, the pullback curve of the pressure wire under maximum hyperaemia is used to detect the target lesion with the largest ΔFFR. After stenting the target lesion, a repeat measurement of pullback recordings of FFR is conducted10,11,12. The concept of this strategy was named “the rule of big delta” by Park et al11.

We consider that the existence of an intra-stent pressure gradient after intervention makes the prediction even more difficult13,14,15,16. In the present study, we developed an equation which predicts the post-intervention FFR in the diffuse/sequential coronary lesion by considering the residual intra-stent FFR gradient (Equation B). Equation B predicted the post-intervention FFR with a 1.3±1.0% error in the in vitro experiment. The study results indicate that the equation was almost perfect for predicting the post-intervention FFR in in vitro coronary circulation. However, the prediction error was 8.0±7.2% in the clinical data analysis, which was considered too large to be used in clinical practice. The results indicate that physicians need to conduct multiple pullback recordings of FFR in the treatment of a diffuse/sequential lesion based on “the rule of big delta”.

Several reasons are proposed for the large prediction error which was observed in the clinical data analysis while the error was minimal in the in vitro study. First, keeping a steady state of maximal hyperaemia is mandatory during a pressure wire pullback for the assessment of diffuse/serial coronary lesions, while the FFR value is usually fluctuating during continuous infusion of intravenous adenosine23,24. Thus, the FFR pullback curve is inevitably affected by the fluctuation of maximal hyperaemia, which causes a considerable error in predicting the post-intervention FFR in a diffuse/sequential coronary lesion. Second, the pressure wire was visually co-registered with angiography in this analysis. The operators were required to observe the pressure wire pullback curve and angiographic information at the same time and visually co-register the two pieces of information, which could represent the cause of prediction error. Third, Equation B includes 4 independent variables. All these variables are influenced by many factors in vivo, including the nervous system, the cardiovascular humoral factor, and stimuli during the procedure. Even small errors of each variable eventually become large errors in Equation B. In post-intervention iFR prediction, the equation includes only two variables, which is considered the great advantage of iFR.

Limitations

Several limitations exist in the present study. First, the in vitro coronary circulation model differed from the complex human coronary circulation in many ways. The model had no side branches between stenoses, and a single large collateral artery connected the donor and recipient arteries. Coronary arteries are not uniformly smooth like silicone tubes. These differences limit the direct applicability of an in vitro model to real world coronary physiology. Second, the clinical data analysis was retrospectively conducted; therefore the accuracy of data acquisition might be inferior to a prospective study. Third, the sample size of the present study was relatively small for both in vitro and clinical data sets. Fourth, coronary wedge pressure measurements were conducted during balloon dilatation without the continuous infusion of adenosine. Several studies reported that maximal hyperaemia can be induced by balloon occlusion of the coronary artery17,25, but the coronary occlusive hyperaemia might make a small difference that could affect the prediction of post-intervention FFR in diffuse/sequential coronary stenosis.

Conclusions

Prediction of post-intervention FFR in a diffuse/sequential lesion is only possible in an in vitro model of coronary circulation. In clinical practice, prediction is difficult due to considerable errors even when the residual intra-stent pressure gradient is considered. Physicians need to conduct multiple pullback recordings of FFR in the treatment of a diffuse/sequential lesion if they prefer to use FFR over resting indices.

Impact on daily practicePrediction of post-intervention fractional flow reserve (FFR) in a diffuse/sequential lesion is only possible in an in vitro model. In clinical practice, prediction is difficult due to considerable errors even when residual intra-stent pressure gradient is considered. Physicians need to conduct multiple pullback recordings of FFR in the treatment of a diffuse/sequential lesion to obtain post-intervention FFR. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Sumiko Horie and Mr. Shiichi Hamaguchi for their advice regarding the in vitro experiments. Special thanks also goes to Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.